Rumors have it that the movie version of X Files may have something to do with specially bred bees used to deliver a deadly viral plague. In part to forestall the routine trivialization and distortion of important historical realities which often accompany that show, Steamshovel Press offers a real life look at the possibility of insect-borne viruses. It comes from Colonel Frank H. Schwable, a US pilot captured by the Koreans during the Korean War who confessed to his role in a bacteriological warfare project that utilized populations of germ-infested flies and mosquitos dropped on the enemy in bombs, replete with miniature parachutes.

The story has another angle, however. It might have been coerced from Schwable under Korean brainwashing torture. Other airman captured during the Korean War claimed that similar "confessions" were forced from them.

After Korean complaints over the germ bug bombs, promised investigations by the International Red Cross and the World Health Organization never materialized. A 1952 scientific commission, which had as a member a witness to WWII Japanese germ warfare who spoke fluent Chinese, concluded that the charges were true. A preliminary investigation of Schwable after the war went nowhere. Secret post- WWII deals between the US and the infamous Shiro Ishii's Unit 731, the germ warfare program of imperial Japan, are documented by Jonathan Vankin in in Steamshovel Press #9.

Authors Jon Holliday and Bruce Cummings note in their history, Korea The Unknown War (Pantheon, 1988) that "The argument that probably carried the most weight [that Schwabel's charges were false] was that the USA could not have used a weapon as horrible as germ warfare, though nothing can be established by this assertion. The USA was engaged in germ-warfare research. It has employed Japanese and Nazi germ-warfare experts and was at the time rushing through work on the nerve gas Sarin, a chemical weapon that was banned by the Geneva convention. The evidence shows preparations for using germ warfare (which do not prove anything about whether it was used or not.)" Sarin gas, of course, is chemical weapon of choice for the Aum Shinrokyo sect.

Interestingly, after the Korean War US church groups began the Heifer Project, a program to rebuild the Korean insect population lost to the widespread use of DDT. It shipped over planeloads of honey bees.

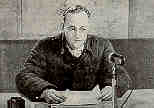

The [North Korean] Hsinhua Agency has made public the following full text of the signed deposition made by Colonel Frank H. Schwable, Chief of staff of the U.S. First Marine Aircraft Wing, disclosing the strategic plan and aims of the American Command in waging germ warfare in Korea.

I am Colonel Frank H. Schwable, 04429, and was Chief of Staff of the First Marine Aircraft Wing until shot down and captured on July 8, 1952. My service with the Marine Corps began in 1929 and I was designated an aviator in 1931, seeing duty in many parts of the world. Just before I came to Korea, I completed a tour of duty in the Division of Aviation at Marine Corps Headquarters.

DIRECTIVE OF THE JOINT CHIEFS OF STAFF

I arrived in Korea on April 10, 1952, to take over my duties as Chief of Staff of the First Marine Aircraft Wing. All my instructions and decisions were subject to confirmation by the Assistant Commanding General, Lamson-Scribner. Just before I assumed full responsibility for the duties of Chief of Staff, General Lamson-Scribner called me into his office to talk over various problems of the Wing. During this conversa- tion he said: "Has Binney given you all the background on the special missions run by VMF-513?" I asked him if he meant "suprop" (our code name for bacteriological bombs) and he confirmed this. I told him I had been given all the background by Colonel Binney.

Colonel Arthur A. Binney, the officer I relieved as Chief of Staff, had given me, as his duties required that he should, an outline of the general plan of bac- teriological warfare in Korea and the details of the part played up to that time by the First Marine Air- craft Wing.

The general plan for bacteriological warfare in Korea was directed by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff in October, 1951. In that month the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent a directive by hand to the Com- manding General, Far East Command (at that time General Ridgway), directing the initiation of bac- teriological warfare in Korea on an initially small, experimental stage but in expanding proportions.

This directive was passed to the Commanding Gen- eral, Far East Air Force, General Weyland, in Tokyo. General Weyland then called into personal conference General Everest, Commanding General of the Fifth Air Force in Korea, and also the Commander of the Nineteenth Bomb Wing at Okinawa, which unit operates directly under FEAF.

The plan that I shall now outline was gone over, the broad aspects of the problem were agreed upon and the following information was brought back to Korea by General Everest, personally and verbally, since for security purposes it was decided not to have anything in writing on this matter in Korea and subject to pos- sible capture.

OBJECTIVES

The basic objective was at that time to test, under field conditions, the various elements of bacteriological warfare, and to possibly expand the field tests, at a later date, into an element of the regular combat operations, depending on the results obtained and the situation in Korea.

The effectiveness of the different diseases available was to be tested, especially for their spreading or epidemic qualities under various circumstances, and to test whether each disease caused a serious disrup- tion to enemy operations arid civilian routine or just minor inconveniences, or was contained completely, causing no difficulties.

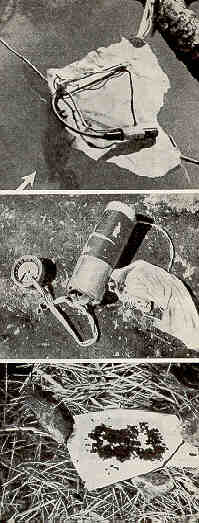

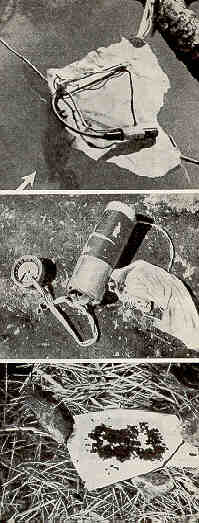

Various types of armament or containers were to be tried out under field conditions and various types of aircraft were to be used to test their suitability as bacteriological bomb vehicles.

Terrain types to be tested included high areas, seacoast areas, open spaces, areas enclosed by moun- tains, isolated areas, areas relatively adjacent to one another, large and small towns and cities, congested it's and those relatively spread out. These tests were to be extended over an unstated period of time but sufficient to cover all extremes of temperature found in Korea.

All possible methods of delivery were to be tested as well as tactics developed to include initially night attack and then expanding into day attack by special- ized Squadrons Various types of bombing were to be tried out, and various combinations of bombing, from single planes up to and including formations of planes, were to be tried out, with bacteriological bombs used in conjunction with conventional bombs. Enemy reac- tions were particularly to be tested or observed by any means available to ascertain what his counter- measures would be, what propaganda steps he would take, and to what extent his military operations would be affected by this type of warfare.

Security measures were to be thoroughly tested- both friendly and enemy. On the friendly ride, all pos- sible steps were to be taken to confine knowledge of the use of this weapon and to control information on the subject. On the enemy side, every possible means was to be used to deceive the enemy and prevent his actual proof that the weapon was being used.

Finally, if the situation warranted, while continuing the experimental phase of bacteriological warfare according to the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive, it might be expanded to become a part of the military or tactical effort in Korea.

INITIAL STAGE

The B-29s from Okinawa began using bacteriolog- ical bombs in November, 1951, covering targets all over North Korea in what might be called random bombing. One night the target might be in Northeast Korea and the next night in Northwest Korea. Their bacteriological bomb operations were conducted in combination with normal night armed reconnaissance as a measure of economy and security.

Early in January 1952, General Schilt, then Com manding General of the First Marine Aircraft Wing, was called to Fifth Air Force Headquarters in Seoul, where General Everest told him of the directive issued by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and ordered him to have VMF-513-Marine Night Fighter Squadron 513 of Marine Aircraft Group 33 of the First Marine Aircraft Wing-participate in the bacteriological warfare program. VMF-513 was based on K8, the Air Force base at Kunsan of the Third Bomb Wing, whose B-26s had already begun bacteriological operations. VMF-513 was to be serviced by the Third Bomb Wing.

While all marine aircraft (combat types) shore based in Korea operate directly under the Fifth Air Force, with the First Marine Aircraft Wing being kept in- formed of their activities, when a new or continuing program is being initiated, the Fifth Air Force normally has initially informed the Wing as a matter of courtesy.

Towards the end of January 1952, Marine night fighters of Squadron 513, operating as single planes on night armed reconnaissance, and carrying bacteriological bombs, shared targets with the B-26s covering the lower half of North Korea with the greatest emphasis on the western portion. Squadron 513 coordinated with the Third Bomb Wing on all these missions, using F7F aircraft (Tiger Cats) because of their twin engine safety.

K8 (Kunsan) offered the advantage of take-off directly over the water, in the event of engine failure, and both the safety and security of over-water flights to enemy territory.

For security reasons, no information on the types of bacteria being used was given to the First Marine Aircraft Wing.

In March 1952, General Schilt was again called to Fifth Air Force Headquarters and verbally directed by General Everest to prepare Marine Photographic Squadron I (VMJ-1 Squadron) of Marine Aircraft Group 33, to enter the program. VMJ-1 based on K3, Marine Aircraft Group 33's base at Pohang, Korea, was to use F2H-2P photographic reconnaissance aircraft (Banshees).

The missions would be intermittent and combined with normal photographic missions and would be scheduled by the Fifth Air Force in separate, top-secret orders.

The Banshees were brought into the program because of their specialized operations, equipment, facilities and isolated area of operations at K3. They could penetrate further into North Korea as far as enemy counteraction is concerned and worked in two-plane sections involving a minimum of crews and disturb- ance of normal missions. They could also try out bombing from high altitudes in horizontal flight in conjunction with photographic runs.

During March 1952, the Banshees of Marine Photo- graphic Squadron 1 commenced bacteriological operations, continuing and expanding the bacteriological bombing of North Korean towns, always combining these operations with normal photographic missions. Only a minimum of bomb supplies were kept on hand to reduce storage problems, and the Fifth Air Force sent a team of two officers and several men to Y\3 (Pohang) to instruct the marine specialists in handling the bombs.

The Navy's part in the program was with the F9Fs (Panthers), ADs (Skyraiders) and standard F2Hs (Banshees), which as distinct from the photographi-- configuration, used carriers off the east coast of Korea.

The Air Force had also expanded its own operations to include squadrons of different type aircraft, with different methods and tactics of employing bacteriological warfare.

This was the situation up to my arrival in Korea. Subsequent thereto, the following main events took place.

OPERATIONAL STAGE

During the latter part of May 1952, the new Commanding General of the First Marine Aircraft Wing, General Jerome, was called to Fifth Air Force Headquarters and given a directive for expanding bac- teriological operations. The directive was given personally and verbally by the new Commanding General of the Fifth Air Force, General Barcus.

On the following day, May 25, General Jerome out- lined the new stage of bacteriological operations to the Wing staff at a meeting in his office at which I was present in my capacity as Chief of Staff.

The other staff members of the First Marine Air- craft Wing present were: General Lamson-Scribner, Assistant Commanding General;, Colonel Stage, Inter- ligence Officer (G2); Colonel Wendt, Operations Officer (G3) and Colonel Clark, Logistics Officer (G4). The directive from General Barcus, transmitted to and discussed by us that morning, was as follows:

A contamination bell was to be established across Korea in an effort to make the interdiction program effective in stopping enemy supplies from reaching the front lines. The Marines would take the left flank of this belt, to include the two cities of Sinanju and Kunuri and the area between and around them. The remainder of the belt would be handled by the Air Force in the centre and the Navy in the east or right flank.

Marine Squadron 513 would be diverted from its random targets to this concentrated target, operating from K8 (Kunsan) stiff serviced by the Third Bomb Wing, using F7Fs (Tiger Cats) because of their twin engine safety. The Squadron was short of these aircraft but more were promised.

The responsibility for contaminating the left flank and maintaining the contamination was assigned to the Commander of Squadron 513, and the schedule of operations left to the Squadron's discretion, subject to the limitations that:

The initial contamination of the area was to be completed as soon as possible and the area must then be recontaminated or replenished at periods not to exceed ten days.

Aircraft engaged on these missions would be given a standard night armed reconnaissance mission, usually in the Haeju Peninsula. On the way to the target, however, these planes would go via Sinanju or Kunuri, drop their bacteriological bombs and then complete their normal missions. This would add to the security and interfere least with normal missions.

Reports on this program of maintaining the contamination belt would go direct to the Fifth Air Force, reporting normal mission numbers so-and-so had been completed "via Sinanju" or "via Kunuri" and stating how many "superpropaganda" bombs had been dropped. Squadron 513 was directed to make a more accurate "truck count" at night than had been customary in order to determine or defect any significant change in the flow off traffic through its operating area.

General Barcus also directed that Marine Aircraft Group 12 of the First Marine Aircraft Wing was to prepare to enter the bacteriological program. First the ADs (Skyraiders) and then the F4Us (Corsairs) were to take part in the expanded program, initially, how- ever, only as substitute for the F7Fs...

General Jerome further reported that the Fifth Air Force required Marine Photographic Squadron I to continue their current bacteriological operations, oper- ating from K3 (Pohang). At the same time Marine Aircraft Group 33 at K3 was placed on a stand-by, last resort, basis. Owing to the distance of K3 from the target area, - large-scale participation in the, program by Marine Aircraft Group 33 was not desired. Because the F9Fs (Panthers) would only be used in an emergency, no special bomb supply would be established over and above that needed to supply the photographic reconnaissance aircraft. Bombs could be brought up from Ulsan in a few hours- if necessary. The plans and the ramifications thereof were discussed at General Jerome's conference and arrangements made to transmit the directive to the officers concerned with carrying out the new program.

It was decided that Colonel Wendt would initially transmit this information to the commanders concerned and the details could be discussed by the cognizant staff officers as soon as they were worked out.

FIRST MAW'S OPERATIONS

Marine Night Fighter Squadron 513 Next day then, May 26, Colonel Wendt held a conference with the Commanding Officer of Squadron 513 and, I believe, the K8 Air Base Commander and the Commanding Officer of the Third Bomb Wing, and discussed the various details.

The personnel of the Fifth Air Force were already cognizant of the plan, having been directly informed by Fifth, Air Force Headquarters.

Since the plan constituted for Squadron 513 merely a change of target and additional responsibility to maintain their own schedule of contamination of their area, there were no real problems to be solved.

During the first week of June, Squadron 513 started operations on the concentrated contamination belt, using cholera bombs. (The plan given to General Jerome indicated that at a later, unspecified date-depend- ing on the results obtained, or lack of results-yellow fever and then typhus in that order would probably he tried out in the contamination belt.)

Squadron 513 operated in this manner throughout June and during the first week in July that I was with the Wing, without any incidents of an unusual nature.

An average of five aircraft a night normally covered the main supply routes along the western coast of Korea up to the Chong Chon River but with emphasis on the area from Phyngyang southward. They diverted as necessary to Sinanju or Kunuri and the area between in order to maintain the ten-day bacteriological replenishment cycle.

We estimated that if each airplane carried two bacteriological bombs, two good nights were ample to cover both Sinanju and Kunuri and a third night would cover the area around and between these cities.

About the middle of June, as best I remember, the Squadron received a modification to the plan from the U.S. Fifth Air Force via the Third Bomb Wing. This new directive included an area of about ten miles surrounding the two principal cities in the Squadron's schedule, with particular emphasis on towns or hamlets on the lines of supply and any by-pass roads.

Marine Aircraft Group 12

Colonel Wendt later held a conference at K6 (Pyongtaek) at which were present the Commanding Officer, Colonel Gaylor, the Executive Officer and the Operations Officer of Marine Aircraft Group 12. Colonel Wendt informed them that they were to make preparations to take part in the bacteriological opera- tions and to work out security problems which would become serious if they got into daylight operations and had to bomb up at their own base K6. They were to inform the squadron commanders concerned but only the absolute barest number of a additional personnel, and were to have a list of a limited number of hand-picked pilots ready to be used on short notice. Colonel Wendt informed them that an Air Force team would soon be provided to assist with logistic problems, this team actually arriving the last week in June.

Before my capture on July 8, both the ADs (Skyraid- ers) and the F4Us (Corsairs) of Marine Aircraft Group 12 had participated in very small numbers, once or twice, in daylight bacteriological operations as a part of regular scheduled, normal day missions, bomb- ing up at K8 (Kunsan), rendezvousing with the rest of the formation on the way to the target. These missions were directed at small towns in Western Korea along the main road leading south from Kunuri and were a part of the normal interdiction program.

Marine Aircraft Group 33

Colonel Wendt passed the plan for the Wing's participation in bacteriological operations to Colonel Condon, Commanding Officer of Marine Aircraft Group 33, on approximately May 27-28.

Since the Panthers (F9Fs) at the Group's base at Pohang would only be used as last resort aircraft, it was left to Colonel Condon's discretion as to just what personnel he would pass the information on to but it was to be an absolute minimum.

During the time I was with the Wing, none of these aircraft had been scheduled for bacteriological missions, though the photographic reconnaissance planes of the Group's VMJ-1 Squadron continued their missions from that base.

SCHEDULING AND SECURITY

Security was by far the most pressing problem affecting the First Marine Aircraft Wing, since the operational phase of bacteriological warfare, as well as other types of combat operations, is controlled by the Fifth Air Force.

Absolutely nothing could appear in writing on the subject. The word "bacteria" was not to be mentioned in any circumstances in Korea, except initially to identify "superpropaganda" or "suprop."

Apart from the routine replenishment operations of Squadron 513, which required no scheduling, bacterio- logical missions were scheduled by separate, top- secret, mission orders (or "FRAG" orders). These stated only to include "superpropaganda" or "suprop" on mission number so-and-so of the routine secret "FRAG" order for the day's operations. -Mission reports went back the same way by separate, top- secret dispatch, stating the number of "suprop" bombs dropped on a specifically numbered mission.

Other than this, Squadron 513 reported their bac- teriological missions by adding "via Kunuri" or "via Sinanju" to their normal mission reports.

Every means was taken to deceive the enemy and to deny knowledge of these operations to friendly personnel, the latter being most important since 300 to 400 men of the Wing are rotated back to the United States each month.

Orders were issued that bacteriological bombs were only to be dropped in conjunction with ordinary bombs or napalm, to give the attack the appearance of a normal attack against enemy supply lines. For added security over enemy territory, a napalm bomb was to remain on the aircraft until after the release of the bacteriological bombs so that if the aircraft crashed it would almost certainly burn and destroy the evidence.

All officers were prohibited from discussing the subject except officially and behind closed doors. Every briefing was to emphasize that this was not only a military secret, but a matter of national policy.

I personally have never heard the subject mentioned or even referred to outside of the office, and I ate all of my meals in the Commanding General's small private mess, where many classified matters were dis- cussed.

ASSESSMENT OF RESULTS

In the Wing, our consensus of opinion was that results of these bacteriological operations could not be accurately assessed. Routine methods of assessment are by (presumably) spies, by questioning prisoners of war, by watching the nightly truck count very carefully to observe deviations from the normal, and by ob- serving public announcements of Korean and Chinese authorities upon which very heavy dependence was placed, since it was felt that no large epidemic could occur without news leaking out to the outside world and that these authorities would, therefore, announce it themselves. Information from the above sources is cor- related at the Commander-in-Chief, Far East level in Tokyo, but the over-all assessment of results is not passed down to the Wing level, hence the Wing was not completely aware of the results.

When I took over from Colonel Binney I asked him for results or reactions up to date and he specifically said: "Not worth a damn."

No one that I know of has indicated that the results are anywhere near commensurate with the effort, danger and dishonesty involved, although the Korean and Chinese authorities have made quite a public report of early bacteriological bomb efforts. The sum total of results known to me are that they are disappointing and no good.

PERSONAL REACTIONS

I do not say the following in defence of anyone, myself included, I merely report as an absolutely direct observation that every officer when first informed that the United States is using bacteriological warfare in Korea is both shocked and ashamed.

I believe, without exception, we come to Korea as officers loyal to our people and government and believing what we have always been told about bacteriolog- ical warfare that it is being developed only for use in retaliation in a third world war.

For these officers to come to Korea and find that their own government has so completely deceived them by still proclaiming to the world that it is not using bacteriological warfare, makes them question mentally all the other things that the government proclaims about warfare in general and in Korea.

None of us believes that bacteriological warfare has any place in war since of all the weapons devised bacteriological bombs alone have as their primary objective casualties among masses of civilians-and that is utterly wrong in anybody's conscience. The spreading of disease is unpredictable and there may be no limits to a fully developed epidemic. Additionally, there is the awfully sneaky, unfair sort of feeling of dealing with a weapon used surreptitiously against an unarmed and unwarned people.

I remember specifically asking Colonel Wendt what were Colonel Gaylor's reactions when he was first in- formed and he reported to me that Colonel Gaylor was both horrified and stupefied. Everyone felt like that when they first heard of it, and their reactions are what might well be expected from a fair-minded, self-respecting nation of people.

Tactically, this type of weapon is totally unwarranted-it is not even a Marine Corps weapon-morally it is damnation itself; administratively and logistically as planned for use, it is hopeless; and from the point of view of self-respect and loyalty, it is shameful.

F. H. Schwable, 04429 Colonel, U.S.M.C. 6 December, 1952