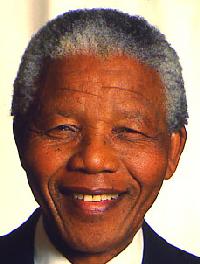

By all accounts no-one had heard of the FAPLA or "Front African People's Liberation Army" until news of it surfaced in early 1998. And even the first accounts of this non-existent organization were plagued by suspicion; its disclosure was in connection with a false report given to President Nelson Mandela by apartheid-era general, George Meiring.

The general, since resigned, was then head of the nation's defense forces. What he was thinking when he advanced the tainted military intelligence document to Mandela? Was he too short-sighted to foresee how averse Mandela would be to the report's coup-plotting accusations? Who wooed the general into giving Mandela the report? And who, precisely, wrote the report and what are its sources? Unnamed sources tell us that intelligence reports such as this never name sources, not even when given to the president.

Members of this illusory FAPLA, the Meiring Report flatly stated, would assassinate the president, murder judges, occupy parliament and broadcast stations and cause enough general unrest to make the country ungovernable in a way that would play into the hands of this left-wing group. A more plausible scenario holds that the report was designed as a diversion to draw attention away from the old-guard intelligence types, many of whom are sympathetic to the growing Afrikaner homeland movement and who perpetrate special operations themselves.

One-hundred and thirty names were listed as members of this mythical, coup-plotting FAPLA, including Mandela's ex-wife Winnie; the deputy chief of the defense forces, Lt. General Siphiwe Nyanda, and other "black soldiers;" the controversial diplomat Robert McBride who was apparently framed to make the report seem credible; Bantu Holomisa and other former and present African National Congress leaders. Even Michael Jackson was said to be in on the plot.

The shroud of controversy surrounding the report inevitably obligated Mandela to appoint an inquiry: judges who trashed the report as "utterly fantastic."

While explicitly denying any acknowledgment of acting wrongly or with sinister motives, on April 6, 1998, General Meiring announced that he asked President Mandela to suspend his contract at the end of May and allow him to retire on early pension without prejudice.

Back in February, when the false report was given to him, Mandela might not have given it so much thought if word of its existence hadn't leaked to the press. Parliament needed reassurances; Mandela was obligated to speak about it, and he generally gets high marks for allowing opposition leaders to read the report in his office. But a strange twist in fate for Robert McBride was keeping the story alive. While in Mozambique investigating gun-running, McBride, a notoriously dangerous man who was once sentenced for bombing a Durban beach bar and killing three women, was himself arrested on March 10. He was accused by local authorities of buying guns to smuggle to South Africa. Then, as McBride languished in a Maputo jail, reports began to surface about South African Police Superintendent Lappies Labushagne's involvement in framing McBride in concert with his Mozambiqan colleagues. Labuschagne ultimately resigned over the incident.

Another name that emerges in connection with these dirty tricks is Hendrik Christoffel Nel, probably not the author, but quite possibly something like the editor, of the Meiring Report. South African papers paint a gruesome portrait of a man who was once a member of the Civil Co-operation Bureau (a secret hit squad that assassinated anti-apartheid activists) and who now heads the Army's counter-intelligence unit. He was reportedly involved in the shooting of an academic named David Webster and has been described as a "professional leaker." One doesn't have to be easily swayed by conspiracy-mined suspicions to question the innocence of someone who served in the infamous Directorate of Covert Collection, the veritable headquarters of apartheid-era dirty tricks that many suspect was the breeding ground for those involved in the more recent shooting of trains and in the not-so- subtle stoking of taxi violence.

President Mandela, Deputy President Thabo Mbeki and Deputy Intelligence Minister Joe Nhlanla speak of a "third force" comprised of old-guard security operatives who specialize in provocations - the type of operations that cause communities to fight without knowing why. To support their claims, they point to events such as the strange death of police assistant commissioner Leonard Radu, the most senior former African National Congress member to join the new South African Police Service. According to Justice Malala of the Financial Mail, Radu was "alleged to be on the trail of ANC leaders who spied for the National Party government." As unready to fade as these accusations of a third force are, the evidence so far is more episodic than conclusive.

Malala writes convincingly about the faction-ridden conflict resulting from the integration of South Africa's old twelve officially recognized intelligence networks into four new agencies. The National Intelligence Co-ordinating Committee, or NICOC, as its name states, coordinates the four separate agencies and advises the government on intelligence policy. According to Malala, the Meiring Report "should first have gone to NICOC, which would have forwarded it to the relevant Minister for a rigorous examination before it was sent to the Office of the President." Meanwhile, Business Day published unconfirmed reports that Meiring may have discussed the report with Defense Minister Joe Modise who may, they allege, have "deliberately allowed the general to shoot himself in the foot" by recommending that it go to Mandela. Similar logic alleges Mandela used the report as a pretext to appoint Siphiwe Nyanda to Meiring's post.

Third force or no third force, the most plausible scenario is that Meiring took his dirty document to Mandela with the expectation that the president would weaken his party by skewering members in the defense forces and intelligence services who had been named in the report. As fate would have it, it was Meiring who fell on his sword: "My early retirement, therefore, is an effort to restore the trust in and to promote the esprit de corps in the South African National Defence Force." Questions linger... Are the authors of the report still at large? and if so, what is being done to stop them from perpetrating dirty tricks before their next attempt? Are more shake-outs in the South African intelligence community overdue? Tolerance of dissent is a hallmark of democracy but it is unacceptable when enshrouded in the conspiratorial form of special operations, such as this false report.