St. Louis Union Station. Photo by Stanley Barriger Barriger Library Collection at UMSL

Missouri has a long and interesting transportation history. While rivers dominated its early days, the railroads helped the state remain an important crossroads of commerce during the later 19th and into the 20th Centuries. Today, the railroads help Missouri remain an important hub for commerce and growth.

The John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library, a part of the St. Louis Mercantile Library would like to help commemorate the bicentennial of the State of Missouri by presenting some of the important and interesting materials from our collection relating to the railroad history of Missouri. Our holdings cover the earliest days of railroads in the state to current books and reports of the major railroads that continue to help move goods and passengers across the state of Missouri to this day.

We hope you enjoy browsing these items and encourage you to visit the library.

The Early Days

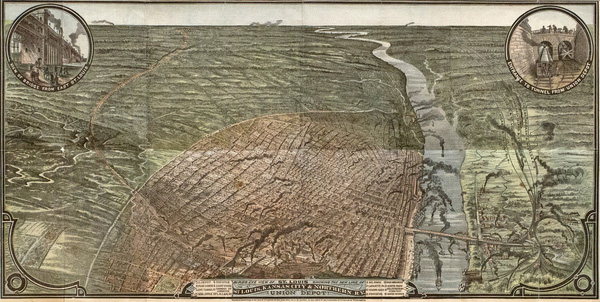

Missouri's existing position as a nexus of commerce along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers made it an important center of trade in the United States. With the development of railroads in the United States during the 1820s, forward thinking citizens saw the potential for the railroad to help speed commerce across the continent. By the 1840s, as railroads from the East were building towards St. Louis and railroads from the Midwest were building towards the East, Missourians began to look Westward to the Pacific and within the state to improve access to natural resources.

A Project for a Railroad to the Pacific by Asa Whitney, 1849

Asa Whitney was a ship captain by trade but is regarded as one of the earliest proponents of a railroad from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. He believed that such a railroad would open up the commercial wealth of the Pacific basin to American Merchants and increase the prosperity of the nation as a whole. This edition of the work was published in 1849, one year after the end of the War with Mexico and the acquisition of thousands of miles of Pacific coastline.

The Hannibal and St. Joseph; Reports of the President, land and Fiscal Agents and Chief Engineer, 1854

The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad was the first railroad to be chartered in the state of Missouri in 1847. It's objective was to connect the city of Hannibal, MO on the Mississippi River with St. Joseph, MO on the Missouri River. The Hannibal and St. Joseph was notable in that it asked the United States Congress for land grants to help build the railroad.

The Pacific Railroad: Memorial and Act of Incorporation, 1850

The Pacific Railroad of Missouri was the St. Louis' and state of Missouri's response to Asa Whitney's and others ideas. While the United States Government was still considering allowing construction of a railroad across federal land in the West, Missouri funded its own first step across the continent. The Pacific Railroad of Missouri would receive state land grants and state support to build a railroad from St. Louis west to Kansas City. This early lead would hopefully encourage the rest of the Pacific Railroad to be built west from Kansas City to the California Coast.

Memorial of the North Missouri Railroad Convention, 1855

The Northern Missouri Railroad was a competitor to both the Hannibal and St. Joseph and the Pacific Railroad of Missouri. This line wanted to connect St. Louis and Kansas City via the rich farmland of the northern part of Missouri. It also had an easier route for construction compared to the Pacific Railroad and marketed itself as a quicker and cheaper way to connect the two cities by rail. This document makes a case for the project along those lines in hopes of getting additional funding.

An Act to Incorporate the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad, 1851

The St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad did not start out as a grand line to cross the state like the Pacific Railroad or the Hannibal and St. Joseph. The St. Louis and Iron Mountain was built to get to the iron deposits around Ironton and Pilot Knob found South of St. Louis. This line would make its money hauling this iron ore to the foundries in St. Louis cheaper and faster than the road and rivers already in use.

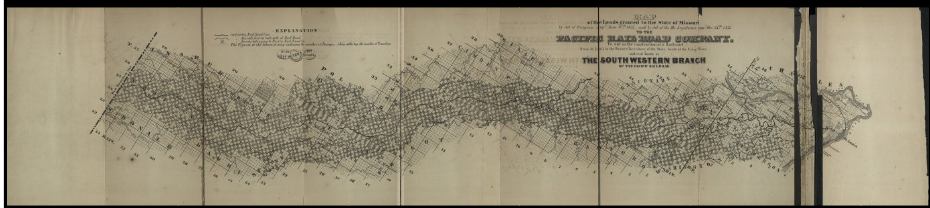

Map of Lands Granted to the Pacific Railroad Company...known as the South Western Branch, 1852

Letter of Prof. Swallow, State Geologist, Upon the Lands and Minerals of South West Missouri, 1857

The success of the St. Louis and Iron Mountain in accessing the mineral wealth of the Ironton area led to the interest in building a branch of the Pacific Railroad of Missouri towards the south-west to access the mineral wealth of the Ozark foothills. This branch would make it to Rolla, MO before the onset of the Civil War.

The 1852 map shows the state land grant given to the Pacific Railroad of Missouri to help it complete the railroad South and West from St. Louis towards the Ozark foothills.

Railroad development in Missouri was hurt by the panic of 1857 and the delays in getting the Pacific Railroad completed and budget overruns forcing the company to keep going to the state for more money. Other railroads in the state found themselves having to work harder to prove their value to the citizens and produce promotional pamphlets like this one produced by the Hannibal and St. Joseph in 1861.

Hannibal and St. Jo. Railroad: Facts and Considerations, 1861

The Civil War

The Civil War was hard on the people and land of Missouri. The state itself was home to a divided population and became known for the violent battles fought between the regular and irregular forces of both sides. The state's railroads were damaged and the state's hope to be the eastern terminus of the Pacific Railroad were dashed when the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act set Council Bluffs, Iowa as the Eastern end of the first Transcontinental Railroad.

For a detailed blow by blow report on how one railroad was affected by the war, one need only read the annual reports for the Pacific Railroad of Missouri from 1862-1865:

1864 (no printed report found)

After the Civil War

The Panic of 1857 and the Civil War slowed down or stopped railroad construction in Missouri until 1865.

Sixteenth Annual Report of the Pacific Railroad of Missouri, 1866

This was the first annual report for the Pacific Railroad after it was completed on September 19, 1865. For the first time in history it was no possible to take a train from downtown St. Louis, MO to downtown Kansas City, MO and not have to transfer to a coach or steamboat during the journey.

Here's a conductor's passenger tariff from 1866 that shows how much it cost to use the Pacific Railroad of Missouri to travel across the state:

Conductor's Passenger Tariff, Pacific R. R., 1866

With the end of the war, the state was able to begin to recover and railroads that had received land grants were now in a position to sell property again to help improve their traffic levels and bottom lines.

The Hannibal and St. Joseph produced this booklet of maps to show the lands they had for sale in 1868:

As the 1860's progressed, the financial condition of the Pacific Railroad of Missouri brought increased scrutiny from the state of Missouri, which had invested heavily in the company.

Map of the Pacific Railroad and its Connections, 1867

The people of South-West Missouri wanted their own railroad. As the Pacific Railroad of Missouri was not able to continue construction South and West, the decision was made the spin off the branch from Franklin, MO (known as Pacific, MO today) as a separate company.

The State legislature approved this idea and the line was separated from the Pacific Railroad in 1868.

Act to Dispose of the S. W. Pacific R. R.

Shortly after the South West Branch was spun off, it became part of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad Company.

Because of how it was spun off, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad originally only had track to Franklin, MO (Today called Pacific, MO) and used the tracks of the Pacific Railroad of Missouri, itself later reorganized and renamed as the Missouri Pacific, to get into St. Louis, MO.

The Post-War era also saw another spurt of railroad development, much of it brought about by the rush of settlement into the West and the development of the natural resources of that region. In some other cases, it was a resumption of economic development in the South that led to the construction of new railroads.

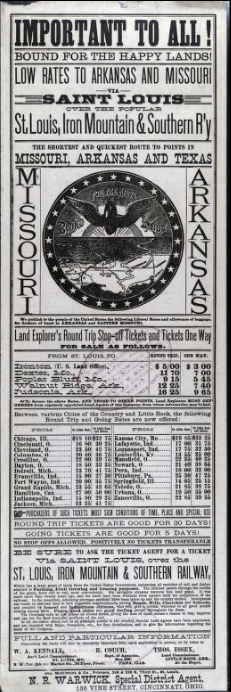

An 1870's broadside promoting settlement in Missouri and Arkansas along the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern.

In 1872, the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad was started in Kansas with the aim to tap into the cattle trade and other goods coming up from Texas towards the industrial areas of the Midwest and the East. It was also hoped that the MK&T would be able to tap into the planned Southern Transcontinental Railroad and bring that traffic towards St. Louis.

The next year, a railroad bridge was built at Louisiana, MO by the Chicago and Alton Railroad as part of that line's attempt to get into Kansas City, MO and bring traffic to Chicago, IL.

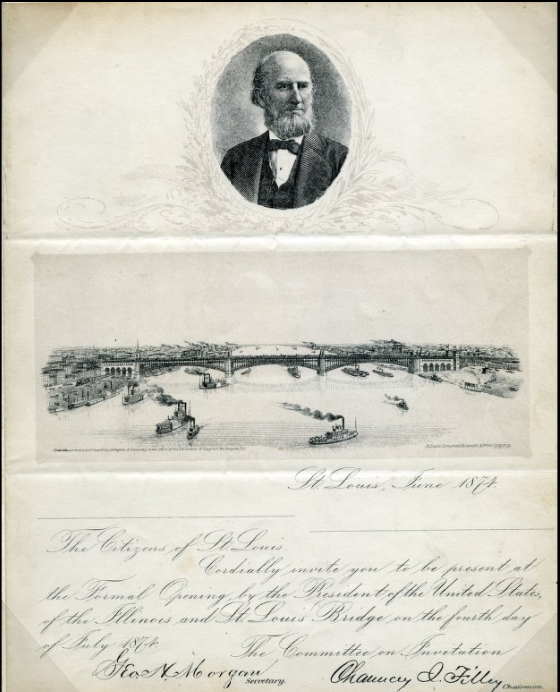

1875 saw the completion of the Eads Bridge in St. Louis, MO giving the city a direct rail connection across the Mississippi.

This same era also saw the influence of financial titans emerge who consolidated railroads into communities of interest and built connections and other lines or reorganized smaller roads into larger systems to help create profitable companies or generate competition for traffic against established carriers.

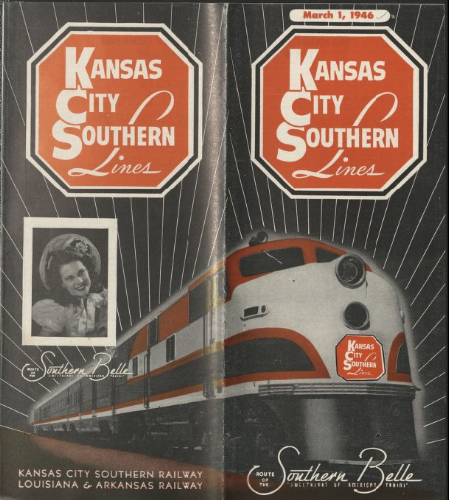

Further West of St. Louis in the late 1880s, Arthur Stillwell created the Kansas City Southern to access the same wealth that the Missouri-Kansas-Texas was seeking. The MKT itself wanted to get into St. Louis and found itself leased to the Missouri Pacific under Jay Gould which gave the Katy access to St. Louis and the other railroads in that city, it had this access at the cost of being a pawn of the Missouri Pacific.

Kansas City became a very attractive location for railroads from the upper Midwest and East to try and reach in the 1880s. Much of this was due to the continued railroad development of the West and Southwest after the Civil War. Railroads from Chicago like the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific, made their way into Missouri specifically to tap into this traffic at Kansas City. (Arriving there in 1887.)

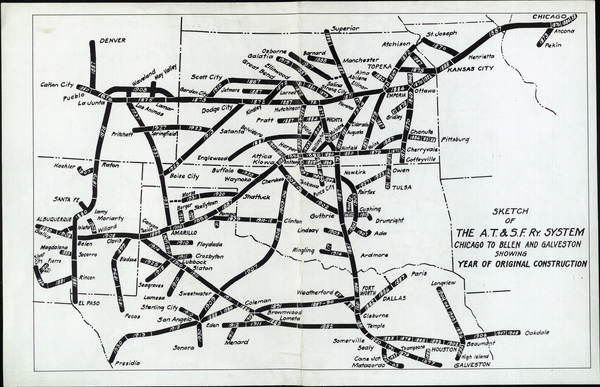

1887 also saw the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe strike out on its own North and West from Kansas City across Northern Missouri towards Chicago. Cyrus Holliday had become President of the Line and wanted to expand the company into the Chicago market on its own rails. The Santa Fe bought a poorly built speculative line in Illinois and pushed it across the Mississippi and then through Missouri to Kansas City.

AT&SF Brochure from 1880 showing the Santa Fe's routes West from Missouri.

While other individual companies were making their way into Missouri, Jay Gould became a dominant player in railroads in Missouri in the 1880s when he took control of the Missouri Pacific, the Texas Pacific, the Saint Louis South Western, the International Great Northern and the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis. Gould had a tarnished reputation from his time as head of the Erie and his attempt to corner the gold market.

An 1883 Timetable for the Missouri Pacific.

In Missouri, Gould helped form the Terminal Railroad and construct St. Louis Union Station, which opened in 1894. This landmark stands to this day.

In 1895, the Katy started building its own main line across the state to relieve itself of the need to use the Missouri Pacific. It was one of several companies that spent the 1890s building lines across the State of Missouri to either access St. Louis or connect Kansas City with Chicago. Unfortunately, much of the line was in a flood plain and was in need of constant maintenance thanks to the Missouri River's floods.

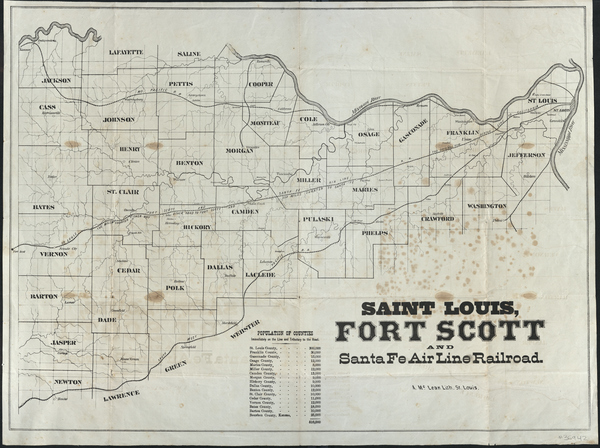

The last railroad to build a line across Missouri between St. Louis and Kansas City was the St. Louis, Kansas and Colorado, which was snapped up by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific. Itself was built along much of a surveyed line of a proposed but never built connection for the Santa Fe called the Saint Louis, Fort Scott and Santa Fe Air Line.

With the completion of the Rock Island's line into St. Louis, there were no more new major trunk lines built across the state.

There was a major change to the railroad landscape as the Interstate Commerce Commission got its first real regulatory teeth in 1907 and soon began to break up the railroad empires of the fanciers of the Gilded Age. This breakup led to a return of more local control of the railroads across the country.

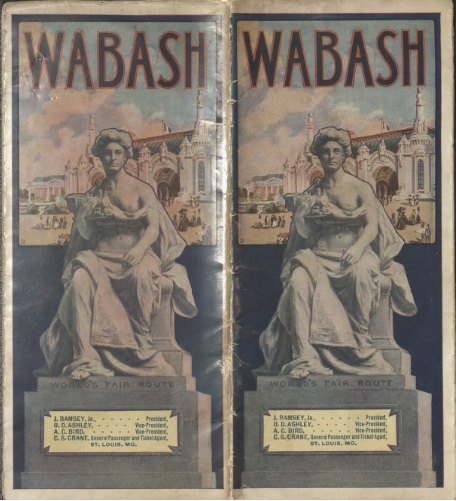

This was also the era of the golden age of passenger trains. Steel cars and the development of dining and sleeping cars and the railroad industry's embracing of passenger traffic led to a long and interesting era of fast trains and colorful promotions. In Missouri, it helped that St. Louis was the site of the World's Fair in 1904 and the first Olympic Games and the railroads of the city worked hard to promote their services.

Wabash 1904 World's Fair Promotional Book. The Wabash main line into St. Louis passed along the southern border of the fair grounds and the company had a station built to serve fair visitors.

St. Louis and San Francisco Timetable from 1907

After the World's Fair in St. Louis, railroads were still moving people and freight across Missouri. Because of St. Louis' location, many railroads promoted their connections with the Southwestern United States.

For the Katy, the link to the Southwest, particularly Texas, was an easy destination to promote, such as in this 1908 Timetable.

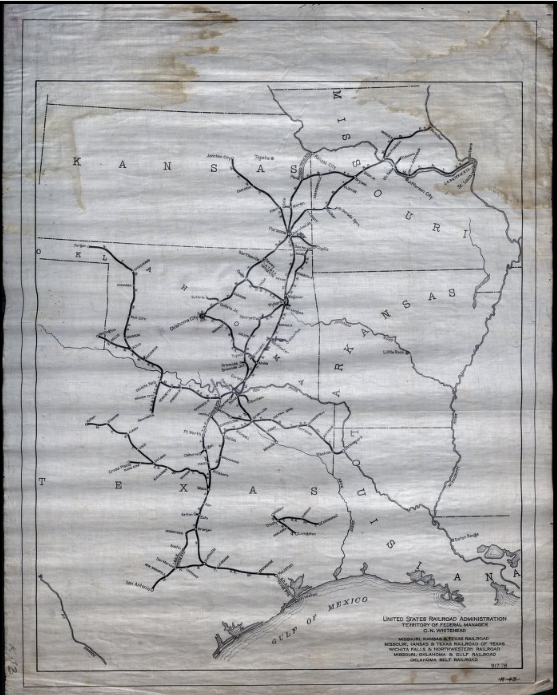

With the outbreak of World War One, the days of recreation travel were on hold. Railroads struggled to handle the load, and complaints about their service led to President Wilson to Nationalize the Railroads under the United States Railroad Administration in 1917.

1919 Map showing the territory of the Federal Manager for the MK&T System.

As the War and concurrent Federal Control ended, the railroads stated that they felt their tax burden was too high and it needed to be matched with the real value of their properties. Before the USRA ended its control of the nation's railroads, Congress funded a massive valuation program that cataloged, mapped and photographed the physical plant of the nation's railroad lines.

Here at the Library we have a set of tentative valuation texts of the railroads from the collection of the Bureau of Railway Economics. Nearly all of these tentative valuation reports are from between 1918 and 1922.

Missouri Pacific Railroad Tentative Valuation Vol 1.; Vol 2.

Tentative Valuation of the Properties of the Saint Louis Southwestern Railway

Tentative Valuation of the Properties of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railway Company Vol. 1; Vol. 2

Tentative Valuations of the Wabash Railway Company...

And this valuation wasn't restricted to just the large railroads, all the railroads were evaluated no matter how small.

Tentative valuation of the property of Mississippi River and Bonne Terre Railway as of June 30, 1914

And with each valuation, a set of maps were made for each line.

Chicago and Alton Valuation Map V.1 MO.-7 Bowling Green, MO., Station 14843+29-14948

A complete set of these final reports, along with nearly all the valuation notebooks and maps collected during this process is available at the US National Archives.

With the end of the War, Travel resumed and railroads resumed their promotional publications.

A 1920's-1930's era brochure from the Frisco about vacationing in the Ozarks

The Missouri Pacific showed passengers that they could go out as far West as California and the Pacific Northwest or into Mexico in this 1934 Timetable.

They also could take passengers to less exotic destinations, like their workplaces.

This post-war boom was set back on its heels by the onset of the Great Depression. The railroad industry was hit especially hard by the economic contractions that wracked the nation. In Missouri, the Missouri Pacific found itself in dire financial straits before it was saved by a loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and a reorganization.

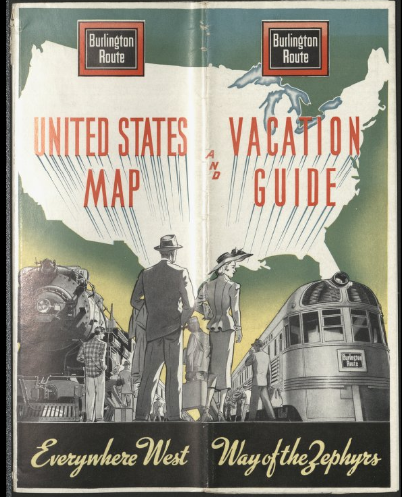

As the economy slowly recovered, the railroads worked to resume their competition for passengers and freight. Here the Burlington Route was promoting vacations along its line in the 1930s and showing off its new Zephyr Diesels.

The Cotton Belt was not a big player compared to the Missouri Pacific or Burlington and had to use other means to entice travelers to take its trains. In this case, air conditioning and meal service.

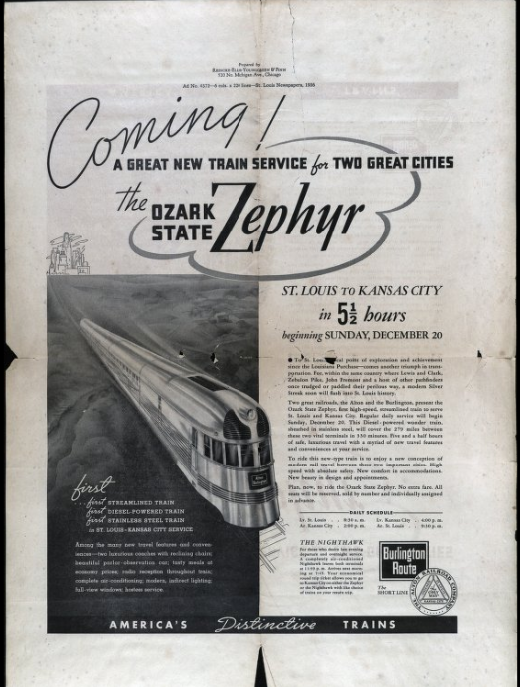

The Alton, which had a line across Missouri from Louisiana, MO to Kansas City, MO was also a lesser competitor compared to the Missouri Pacific and the Burlington for cross-state traffic. It worked with the Burlington to create a joint train called the Ozark State Zephyr to try and help get business in Missouri.

The full 1936 Alton Timetable is here.

But it wasn't just passenger trains being promoted. All companies wanted to increase freight traffic too and promoted the communities they served like in this MK&T publication, as valuable sites for new industries.

The Railroads worked hard to rebuild after World War One and later to survive after the Great Depression. The onset of the Second World War caused railroads to see a great spike in traffic, but the aftermath would lead to major changes in the industry.

Diesel Locomotives began to replace steam on all trains.

Railroad mergers began to ripple across the landscape as well. In Missouri, the Alton Route found itself now part of the Gulf Mobile and Ohio after the war and other railroads across the country also worked to find partners to survive in the new era of truck and auto competition.

But despite these improvements, Americans liked the convenience of the car and the speed of the jet airliner for longer trips.

By the 1960s passenger train timetables became thinner and thinner as trains were canceled or combined.

Here's a Cotton Belt timetable that's down to just two pages:

The Wabash was just as thin

But that doesn't mean that the railroads were just giving up.

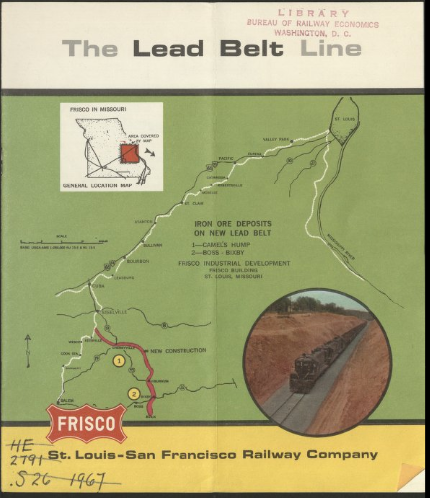

In some cases in the late 1960's new lines were built to serve new industries. Here in Missouri, the Frisco built new lines to serve newly established iron ore mines in the state's historic "Lead Belt."

Here's a Wabash Map showing its service to St. Louis Area Industries in 1964 in an attempt to attract new customers.

And the Reverse is here.

The railroad industry worked hard to survive economic recession in the 1970s and choking federal regulation. The Rock Island was forced into bankruptcy in part because of the long drawn out merger process with the Interstate Commerce Commission. This, along with the Penn Central bankruptcy and formation of Conrail helped spur Congress into overhauling the regulations governing the industry with the Staggers Act of 1981.

As the Staggers Act was being worked on in Washington, here in Missouri one of the oldest railroads in the state was merging with a new partner. The Missouri Pacific applied to merge with the Union Pacific in 1980 and it would be finalized in 1982 creating one of the largest and strongest railroads in the nation.

Title page of the Application from the Union Pacific, Missouri Pacific and Western Pacific merger docket.

The St. Louis and San Francisco was also in the process of merging with the Burlington-Northern in 1980 and once these two mergers were complete, the Kansas City Southern would be the only class 1 railroad left with its headquarters in Missouri.

Further mergers would take place in the 1990s that would lead to the creation of the 7 super railroads of North America and of the 7, 5 would serve Missouri directly and all 7 would connect with the state via St. Louis and its Terminal Railroad.

Since the turn of the 20th Century the railroad industry has matured and now must compete with cars and trucks for passengers and freight. However, they continue to provide important service to the people of Missouri and the nation as a whole and throughout the new challenges they have faced from two world wars, to the rise of the interstate highway system to economic crises and changes in technology. Missouri's railroads will continue to help the people of this state get themselves and their goods across the nation and the world for decades to come.

This project was generously supported by the Union Pacific Foundation.

This project was generously supported by the Union Pacific Foundation.